As I mentioned in my previous post, I will be exploring infrastructure trends, and in particular, cloud computing. But while cloud computing is getting most of the marketing press, there are two additional phenomena that are capturing as much if not more of the market: computer appliances and SaaS. So, before we dive deep into cloud, let’s explore these other two trends and then set the stage for a comprehensive cloud discussion that will yield effective strategies for IT leaders.

Computer appliances have been available for decades, typically in the network, security, database and specialized compute spaces. Firewalls and other security devices have long leveraged an appliance approach where generic technology (CPU, storage, OS) is closely integrated with additional special purpose software and sold and serviced as an packaged solution. Specialized database appliances for data warehousing were quite successful starting in the early 1990s (remember Teradata?).

The tighter integration of appliances gives significant advantage over traditional approaches with generic systems. First, since the integrator of the package often is also the supplier of the software and thus can achieve improved tuning of performance and capacity of the software with a specific OS and hardware set. Further, this integrated stack then requires much less install and implementation effort by the customer. The end result can be impressive performance for similar cost to a traditional generic stack without the implementation effort or difficulties. Thus appliances can have a compelling performance and business case for the typical medium and large enterprise. And they are compelling for the technology supplier as well because they will command higher prices and are much higher margin than the individual components.

It is important to recognize that appliances are part of a normal tug and pull between generic and specialized solutions. In essence, throughout the past 40 years of computing, there has been the constant improvement in generic technologies under the march of Moore’s law. And with each advance there are two paths to take: leverage generic technologies and keep your stack loosely coupled so you can continue to leverage the advance of generic components or, closely integrated your stack with the then most current components and drive much better performance from this integration.

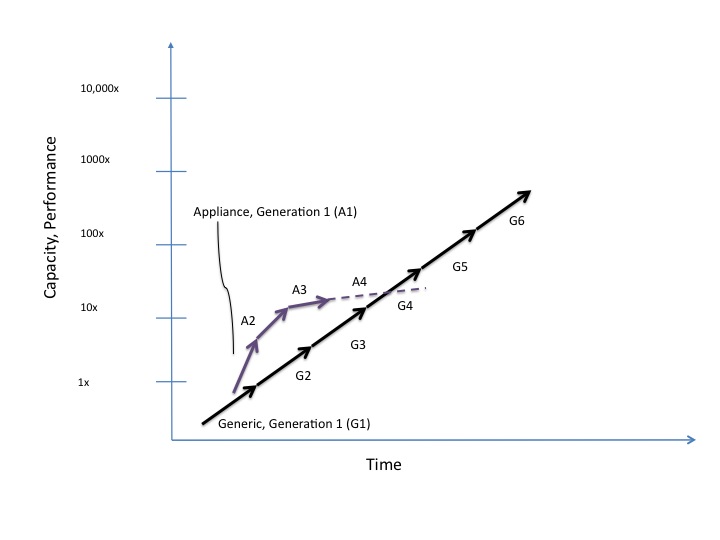

By their very nature though, appliances become rooted in a particular generation of technology. The initial iteration can be done with the latest version of technology but the integration will likely result in tight links to the OS, hardware and other underlying layers to wring out every performance improvement available. These tight links yield both the performance improvement and the chains to a particular generation of technology. Once an appliance is developed and marketed successfully, ongoing evolutionary improvements will continue to be made, layering in further links to the original base technology. And the margins themselves are addictive with the suppliers doing everything possible to maintain the margins (thus evolutionary low cost advances will occur but revolutionary (next generation) will likely require too high of an investment to maintain the margins). This then spells the eventual fading and demise of that appliance, as the generic technologies continue their relentless advance and typically surpass the appliance in 2 or 3 generations. This is represented in the chart below and can be seen in the evolution of data warehousing.

The first instances of data warehousing were done using the primary generic platform of the time (the mainframe) and mainstream databases. But with the rise of another generic technology, proprietary chipsets out of the midrange and high end workstation sector, Teradata and others combined these chipsets with specialized hardware and database software to develop much more powerful data warehouse appliances. From the late 1980s through the 1990s the Teradata appliance maintained a significant performance and value edge over generic alternatives. But that began to fray around 2000 with the continued rise of mainstream databases and server chipsets along with low cost operating systems and storage that could be combined to match the performance of Teradata at much lower cost. In this instance, the Teradata appliance held a significant performance advantage for about 10 years before falling back into or below the mainstream generic performance. The value advantage diminished much sooner of course. Typically, the appliance performance advantage is for 4 to 6 years at most. Thus, early in the cycle (typically 3 to 4 generic generations or 4 to 5 years), an appliance offering will present material performance and possibly cost advantages over traditional, generic solutions.

As a technology leader, I recommend the following considerations when looking at appliances:

- If you have real business needs that will drive significant benefit from such performance, then investigate the appliance solution.

- Keep in mind that in the mid-term the appliance solution will steadily lose advantage and subsequently cost more than the generic solution. Understand where the appliance solution is in its evolution – this will determine its effective life and the likely length of your advantage over generic systems

- Factor the hurdle, or ‘switchback’ costs at the end of its life. (The appliance will likely require a hefty investment to transition back to generic solutions that have steadily marched forward).

- The switchback costs will be much higher where business logic is layered in (e.g. for middleware, database or business software appliances versus network or security appliances (where there is minimal custom business logic layered in).

- Include the level of integration effort and cost required. Often a few appliances within a generic infrastructure will have a smooth integration and less cost. On the other hand, weaving multiple appliances within a service stack can cause much higher integration costs and not yield desired results. Remember that you have limited flexibility with an appliance due to its integrated nature and this could cause issues when they are strung together (e.g., a security appliance with a load balance appliance with a middleware appliance with a business application appliance and data warehouse appliance (!)).

- Note for certain areas, security and network in particular, often the follow-on to an appliance will be a next generation appliance from the same or different vendor. This is because there is minimal business logic incorporated in the system (yes, there are lots of parameter settings like firewall rules customer for a business, but the firewall operates essentially the same regardless of the business that uses it).

With these guidelines, you should be able to make better decisions about when to use an appliance and how much of a premium you should pay.

In my next post, I will cover SaaS and I will then bring these views together with a perspective on cloud in a final post.

What changes or additions would you make when considering appliances? I look forward to your perspective.

Best, Jim Ditmore