As we discussed in our previous post on the inefficient technology marketplace, the typical IT shop spends 60% or more of its budget on external vendors – buying hardware, software, and services. Often, once the contract has been negotiated, signed, and initial deliveries commence, attentions drift elsewhere. There are, of course, plenty of other fires to put out. But maintaining an ongoing, fact-based focus on your key vendors can result in significant service improvement and corresponding value to your firm. This ongoing fact-based focus is proper vendor management.

Proper vendor management is the right complement to a robust, competitive technology acquisition process. For most IT shops, your top 20 or 30 vendors account for about 80% of your spend. And once you have achieved outstanding pricing and terms through a robust procurement process, you should ensure you have effective vendor management practices in place that result in sustained strong performance and value by your vendors.

Perhaps the best vendor management programs are those run by manufacturing firms. Firms such as GE, Ford, and Honda have large dedicated supplier teams that work closely with their suppliers on a continual basis on all aspects of service delivery. Not only do the supplier teams routinely review delivery timing, quality, and price, but they also work closely with their suppliers to help them improve their processes and capabilities as well as identify issues within their own firm that impact supplier price, quality and delivery. The work is data-driven and leverages heavily process improvement methodologies like LEAN. For the average IT shop in services or retail, a full blown manufacturing program may be overkill, but by implementing a modest but effective vendor management program you can spur 5 to 15% improvements in performance and value which accumulate to considerable benefits over time.

The first step to implementing a vendor management program is to segment your vendor portfolio. You should focus on your most important suppliers (by spend or critical service). Focus on the top 10 to 30 suppliers and segment them into the appropriate categories. It is important to group like vendors together (e.g, telecommunications suppliers or server suppliers). Then, if not already in place, assign executive sponsors from your company’s management team to each vendor. They will be the key contact for the vendor (not the sole contact but instead the escalation and coordination point for all spend with this vendor) and will pair up with the procurement team’s category lead to ensure appropriate and optimal spend and performance for this vendor. Ensure both sides (your management and the vendor know the expectations for suppliers (and what they should expect of your firm). Now you are ready to implement a vendor management program for each of these vendors.

So what are the key elements of an effective vendor management program? First and foremost, there should be three levels of vendor management:

- regular operational service management meetings

- quarterly technical management sessions, and

- executive sessions every six or twelve months.

The regular operational service management meetings – which occur at the line management level – ensure that regular service or product deliveries are occurring smoothly, issues are noted, and teams conduct joint working discussions and efforts to improve performance. At the quarterly management sessions, performance against contractual SLAs is reviewed as well as progress against outstanding and jointly agreed actions. The actions should address issues that are noted at the operational level to improve performance. At the nest level, the executive sessions will include a comprehensive performance review for the past 6 or 12 months as well as a survey completed by and for each firm. (The survey data to be collected will vary of course by the product or service being delivered.) Generally, you should measure along the following categories:

- product or service delivery (on time, on quality)

- service performance (on quality, identified issues)

- support (time to resolve issues, effectiveness of support)

- billing (accuracy, clarity of invoice, etc)

- contractual (flexibility, rating of terms and conditions, ease of updates, extensions or modifications)

- risk (access management, proper handling of data, etc)

- partnership (willingness to identify and resolve issues, willingness to go above and beyond, how well the vendor understand your business and your goals)

- innovation (track record of bringing ideas and opportunities for cost improvement or new revenues or product features )

Some of the data (e.g. service performance) will be summarized from operational data collected weekly or monthly as part of the ongoing operational service management activities. The operational data is supplemented by additional data and assessments captured from participants and stakeholders from both firms. It is important that the data collected be as objective as possible – so ratings that are high or low should be backed up with specific examples or issues. The data is then collated and filtered for presentation to a joint session of senior management representing their firms. The focus of the executive session is straightforward: to review how both teams are performing and to identify the actions that can enable the relationship to be more successful for both parties. The usual effect of a well-prepared assessment with data-driven findings is strong commitment and a re-doubling of effort to ensure improved performance.

Vendors rarely get clear, objective feedback from customers, and if your firm provides such valuable information, you will often be the first to reap the rewards. And by investing your time and effort into a constructive report, you will often gain an executive partner at your vendor willing to go the extra mile for your firm when needed. Lastly, the open dialogue will also identify areas and issues within your team and processes, such as poor specifications or cumbersome ordering processes that can easily be improved and yield efficiencies for both sides.

It is also worthwhile to use this supplier scorecard to rate the vendor against other similar suppliers. For example, you can show there total score in all categories against other vendors in an an anonymized fashion (e.g., Vendor A, Vendor B, etc) where they can see their score but can also see other vendors doing better and worse. Such a position often brings out the competitive nature of any group, also resulting in improved performance in the future.

Given the investment of time and energy by your team, the vendor management program should be focused on your top suppliers. Generally, this is the top 10 to 30 vendors depending on your IT spend. The next tier of vendors (31 through 50 or 75) should get an annual or biannual review and risk assessment but not the regular operational meetings or assessments and management assessment unless the performance is below par. Remediation of such a vendor’s performance can often be turned around by applying such a program.

Another valuable practice, once your program is established and is yielding constructive results, is to establish a vendor awards program. With the objective and thoughtful perspective of your vendors, you can then establish awards for your top vendors – vendor of the year, vendor partner of the year, most improved vendor, most innovative, etc. Perhaps invite the senior management of the vendor’s receiving awards to attends and awards dinner, along with your firm’s senior management to give the awards, will further spur both those who win the awards as well as those who don’t. Those who win will pay attention to your every request, those who don’t will have their senior management focused on winning the award for next year. The end result, from the weekly operational meetings, to the regular management sessions, and the annual gala, is that vendor management positively impacts your significant vendor relationships and enables you to drive greater value from your spend.

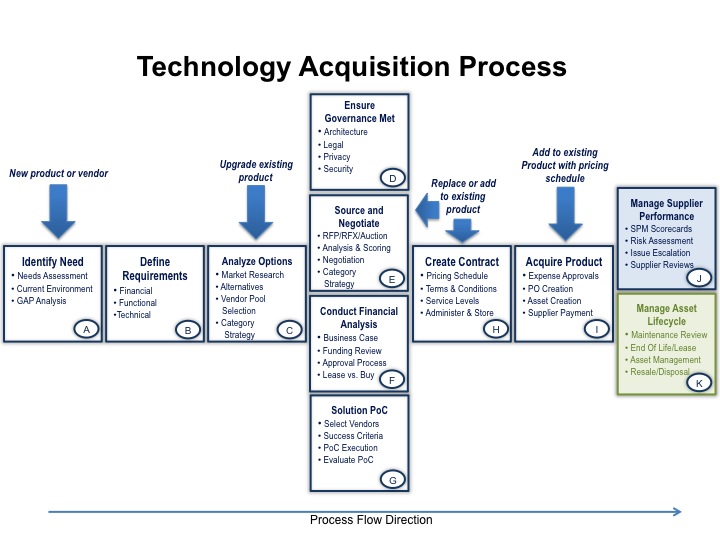

Of course, the vendor management process outlined here is a subset of the procurement lifecycle applied to technology. It complements the technology acquisition process and enables you to repairs or improve and sustain vendor performance and quality levels for a significant and valuable gain for your company.

It would be great to hear from your experience with leveraging vendor management.

Best, Jim Ditmore