Benchmarking is an important tool for management and yet frequently I have found most organizations do not take advantage of it. There seem to be three camps when it comes to benchmarking:

- those who either don’t have the time or through some rationale, avoid tapping into benchmarking

- those that try to use it infrequently but for a variety of reasons, are never able to leverage and progress from its use

- those who use benchmarking regularly and make material improvement

I find it surprising that as so many IT shops don’t benchmark. I have always felt that there were only two possible outcomes from doing benchmarking:

- You benchmark and you find out that you compare very well with the rest of the benchmark population and you can now use this data as part of your report to your boss and the business to let them know the value your team in delivering

- You benchmark and you find out a bunch of things that you can improve. And you now have the specifics as to where and likely how to improve.

So, with the possibility of good results with either outcome, when and how should you benchmark your IT shop?

I recommend making sure that your team and the areas that you want to benchmark have an adequate maturity level in terms of defined processes, operational metrics, and cost accounting. Usually, to take advantage of a benchmark, you should be at a minimum a Level 2 shop and preferably a Level 2+ shop where you have well understood unit costs and unit productivity. If you are not at this level, then in order to compare your organization to others, you will need to first gather an accurate inventory of assets, staff, time spent by activity (e.g., run versus change). This data should supplemented with defined processes and standards for the activity to be compared. And then for a thorough benchmark you will need data on the quality of the activity and preferably 6 month trending of all data. In essence, these are prerequisite activities that must take place before you benchmark.

I do think that many of teams that try to benchmark but then are not able to do much with the results are unable to progress because:

- they do not have the consistent processes on which improvements and changes can be implemented

- they do not routinely collect the base data and thus once the benchmark is over, no further data is collected to understand if any of the improvements had effect or not

- the lack of data and standards results in so much estimation for the benchmark that you cannot then use it to pinpoint the issues

So, rather than benchmark when you are a Level 1 or 2- shop, instead just work on the basics of improving your maturity of your activities. For example, collect and maintain accurate asset data – this foundational to any benchmarking. Similarly collect how your resources spend their time — this is required anyway to estimate or allocate costs to whoever drives it, so do it accurately. And implement process definitions, base operational metrics, and have the team review and publish monthly.

For example, let’s take the Unix server area. If we are looking to benchmark we would want to check various attributes against the industry including:

- number of servers (versus similar size firms in our industry)

- percent virtualized

- unit cost (per server)

- unit productivity (servers per admin)

- cost by server by category (e.g. staff, hardware, software, power/cooling/data center, maintenance)

By having this information you can quickly identify where you have inefficiencies or you are paying too much (e.g., the cost of your software per server) or you are unproductive (your servers per admin is low versus the industry). This then allows you to draw up effective action plans because you are addressing problems that can likely be solved (you are looking to bring your capabilities up to what is already best practice in the industry).

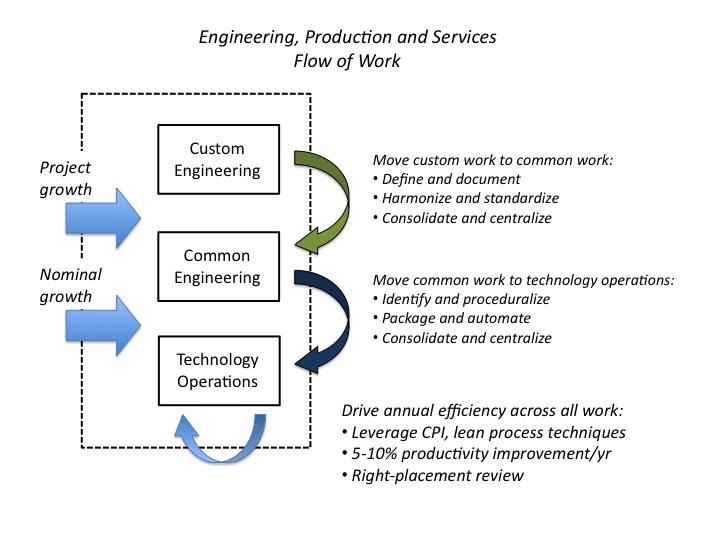

I recall a benchmark of the Unix server area where our staff costs per server were out of line with the industry though we had relatively strong productivity. Upon further investigation we realized we had mostly a very senior workforce (thus being paid the top end of the scale and very capable) that had held on to even the most junior tasks. So we set about improving this in several ways:

- we packaged up and moved the routine administrative work to IT operations (who did it for far less and in a much more automated manner)

- we put in place a college graduate program and shifted nearly all of our hires in this group from a previous focus of mid to senior only new hires to one where it was mostly graduates, some junior and only a very few mid-level engineers.

- we also put in place better tools for the work to be done so staff could be more productive (more servers per admin)

The end result after about 12 months was a staff cost per server that was significantly below the industry median, approaching best in class (and thus we could reduce our unit allocations to the business). Even better, with a more balanced workforce (i.e., not all senior staff) we ended up with a happier team because the senior engineers were now looked up to and could mentor the new junior staff. Moreover, the team now could spend more of their time on complex change and project support rather than just run activities. And with the improved tools making everyone more productive, it resulted in a very engaged team that regularly delivered outstanding results.

I am certain that some of this would have been evident with just a review. But by benchmarking, not only were we able to precisely identify where we had opportunity, we were better able to diagnosis and prescribe the right course of action with targets that we knew were doable.

Positive outcomes like this are the rule when you benchmark. I recommend that you conduct a yearly external benchmark for each major component area of infrastructure and IT operations (e.g. storage, mainframe, server, network, etc). And at least every two years, assess IT overall, assess your Information Security function, and if possible, benchmark your development areas and systems in business terms (e.g., cost per account, cost per transaction).

One possibility in the development area is that since most IT shops have multiple sub-teams within development, you can use the operational development metrics to compare them against each other (e.g. defect rates, cost per man hour or cost per function, etc). Then the sub-team with the best metrics can share their approach so all can improve.

If you conduct regular exercises like this, and combine it with a culture of relentless improvement, you will find you achieve a flywheel effect, where each gain of knowledge and each improvement becomes more additive and more synergistic for your team. You will reduce costs faster and improve productivity faster than taking a less open and less scientific approach.

Have you seen such accelerated results? What were the elements that contributed to that progress? I look forward to hearing from you.

Best, Jim